55 Days in Peking:The Boxer Rebellion

|

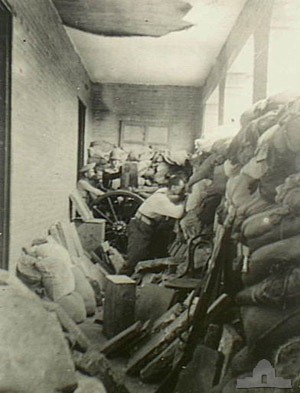

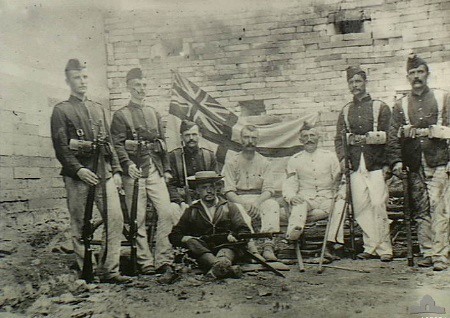

THE FORTIFIED BALCONY OF THE BRITISH MINISTER'S HOUSE WITH A NORDENFELT MACHINE GUN CREW AND A RIFLEMAN |

|

THE FORTIFIED BALCONY OF THE BRITISH MINISTER'S HOUSE WITH A NORDENFELT MACHINE GUN CREW AND A RIFLEMAN |  |

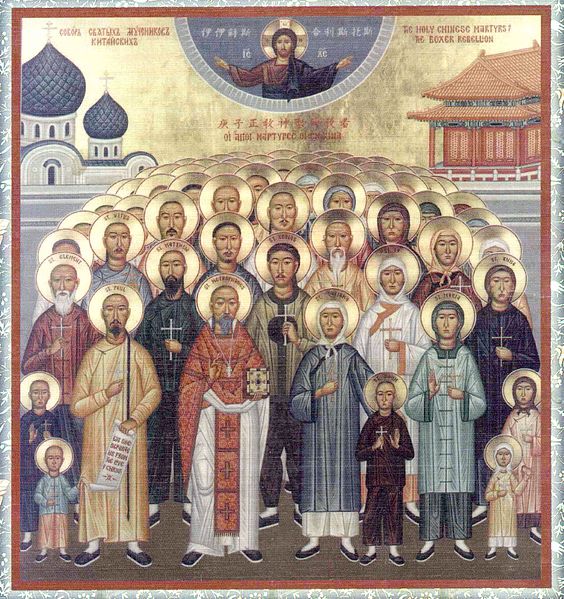

| The Boxer Rebellion

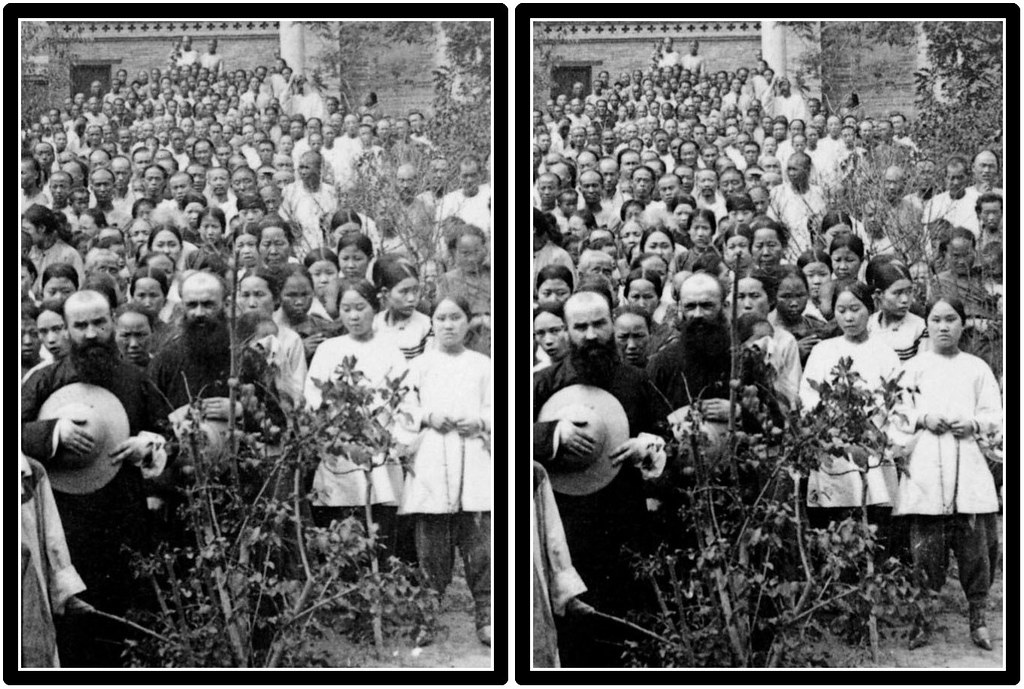

The Boxer Rebellion, Boxer Uprising or Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, proto-nationalist movement by the Righteous Harmony Society in China between 1898 and 1901, opposing foreign imperialism and Christianity. The uprising took place against a background of severe drought and economic disruption in response to growth of foreign spheres of influence. Grievances ranged from political invasion ranging back to the Opium Wars and economic incursions, to missionary evangelism, which the weak Qing state could not resist. Concerns grew that missionaries could use the sponsorship of their home governments and their extraterritorial status to the advantage of Chinese Christians, appropriating lands and property of unwilling Chinese villagers to give to the church. After several months of growing violence against foreign and Christian presence in Shandong and the North China plain, in June 1900, Boxer fighters, convinced that they were invulnerable to foreign weapons, converged on Beijing with the slogan "support the Qing, exterminate the foreigners." They forced foreigners and Chinese Christians to seek refuge in the Legation Quarter. In response to reports of armed foreign landings and demands, the initially hesitant Empress Dowager Cixi, urged by the conservatives of the Imperial Court, supported the Boxers and on June 21 authorized war on foreign powers. Diplomats, foreign civilians and soldiers, and Chinese Christians in the Legation Quarter were under siege by the Imperial Army of China and the Boxers for 55 days. Chinese officialdom was split between those who supported the Boxer effort to destroy the foreigners and those officials seeking diplomatic resolution. Clashes were reported between Chinese factions favoring war and those favoring conciliation, the latter led by Prince Qing. The supreme commander of the Chinese forces, Ronglu, later claimed that he acted to protect the besieged foreigners. The Eight-Nation Alliance, after being initially turned back, brought 20,000 armed troops to China, defeated the Imperial Army, and captured Beijing on August 14, lifting the siege of the Legations. Uncontrolled plunder of the capital and the surrounding countryside ensued, along with the summary execution of those suspected of being Boxers. The Boxer Protocol of 7 September 1901 provided for execution of government officials who had supported the Boxers, provisions for foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and an indemnity of 67 million pounds (450 million taels of silver), more than the government's annual tax revenue, to be paid as indemnity over a course of thirty-nine years to the eight nations involved.[4] Origins of the BoxersThe Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, known by foreigners as the Boxers, or "Yihe Magic Boxing", was a secret society founded in the northern coastal province of Shandong consisting largely of people who had lost their livelihoods due to imperialism and natural disasters.[5] The group originated from the Lí sect of the Ba gua religion group.[6] Foreigners came to call the well-trained, athletic young men "Boxers" due to the martial arts and calisthenics they practiced. The Boxers' primary feature was spirit possession, which involved "the whirling of swords, violent prostrations, and chanting incantations to Taoist and Buddhist spirits."[7] The Boxers believed that through training, diet, martial arts, and prayer they could perform extraordinary feats, such as flight. Further, they popularly claimed that millions of spirit soldiers would descend from the heavens and assist them in purifying China of foreign influences. The Boxers consisted of local farmers/peasants and other workers who were made desperate by disastrous floods and widespread opium addiction and laid the blame on Christian missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Europeans colonizing their country. Missionaries were protected under the policy of extraterritoriality. Chinese Christians were alleged also to have filed false lawsuits.[8] The Boxers called foreigners "Guizi" (鬼子, literally: demons), a deprecatory term, and condemned Chinese Christian converts and Chinese working for foreigners. The Boxers were only lightly armed with rifles and swords, claiming supernatural invulnerability towards blows of cannon, rifle gunshots, and knife attacks. The Boxer beliefs were characteristic of millennarian movements, such as the American Indian Ghost Dance, often rising in societies under extreme stress.[9] Several secret societies in Shandong predated the Boxers. In 1895, Yuxian, a Manchu who was then prefect of Caozhou and would later become provincial governor, acquired the help of the Big Sword Society in fighting against bandits. Although the Big Swords had heterodox practices, they were not seen as bandits by Chinese authorities. Their efficiency in defeating banditry led to a flood of cases overwhelming the magistrates' courts, to which the Big Swords responded by executing the bandits that were apprehended.[10] The Big Swords relentlessly hunted the bandits, but the bandits converted to Catholic Christianity, gaining them legal immunity from prosecution and also placed them under the protection of the foreigners. The Big Swords responded by attacking bandit Catholic churches and burning them.[11] As a result, Yuxian executed several Big Sword leaders, but did not punish anyone else. More secret societies started emerging after this.[12] The early years saw a variety of village activities, not a broad movement or a united purpose. Like the Red Boxing school or the Plum Flower Boxers, the Boxers of Shandong were more concerned with traditional social and moral values, such as filial piety, than with foreign influences. One leader, for instance, Zhu Hongdeng (Red Lantern Zhu), started as a wandering healer, specializing in skin ulcers, and gained wide respect by refusing payment for his treatments.[13] Zhu claimed descent from Ming Dynasty emperors, since his surname was the surname of the Ming Imperial Family. He announced that his goal was to "Revive the Qing and destroy the foreigners" ("Fu Qing mie yang").[14] [edit]Causes of conflict and unrestInternational tension and domestic unrest fueled the growth and spread of the Boxer movement. First, a drought followed by floods in Shandong province in 1897–1898 forced farmers to flee to cities and seek food. As one observer said, "I am convinced that a few days' heavy rainfall to terminate the long-continued drought... would do more to restore tranquility than any measures which either the Chinese government or foreign governments can take."[15] A French political cartoon depicting Chinaas a king cake is about to be carved up byQueen Victoria (Britain), Wilhelm II(Germany), Nicolas II (Russia), Marianne(France), and a samurai (Japan) while aMandarin official helplessly looks on. A major cause of Chinese discontent was the Christian missionaries, both Protestant and Catholic, who came to China in ever increasing numbers. The exemption of missionaries from various laws angered the local Chinese. On 1 November 1897 a band of twenty to thirty armed men stormed into the residence of a German missionary, George Stenz, and killed two priests who were his guests while looking for Stenz, who was sleeping in the servant's quarters. Christian villagers then came to his defense, driving off the attackers. This event was known as the Juye Incident. When Kaiser Wilhelm IIreceived news of these murders, he dispatched the German East Asia Squadron to occupy Jiaozhou Bay on the southern coast of Shandong.[16] In October 1898, a group of Boxers attacked the Christian community of Liyuantun village, where a temple to the Jade Emperor had been converted into a Catholic church. Disputes had surrounded that church since 1869, when the temple had been granted to the Christian residents of the village. This incident marked the first time the Boxers used the slogan "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners" (扶清灭洋) that would later characterize them.[17] Aggression toward missionaries and Christians gained the attention of foreign (mainly European) governments.[18] In 1899, the French Minister in Beijing helped the missionaries to obtain an edict granting official status to every order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, enabling local priests to support their people in legal or family disputes and bypass the local officials. After the German government took over Shandong, many Chinese feared that the missionaries and quite possibly all Christians were imperialist attempts of "carving the melon," i.e., to divide and colonise China piece by piece.[19] A Chinese official expressed the animosity towards foreigners succinctly, "Take away your missionaries and your opium and you will be welcome."[20] The growth of the Boxer movement coincided with the Hundred Days' Reform (11 June–21 September 1898). Progressive Chinese officials, with support from Protestant missionaries, persuaded Emperor Guangxu to institute reforms, which alienated many conservative officials by their sweeping nature. Such opposition from conservative officials led the Empress Dowager to intervene and reverse the reforms. The failure of the reform movement disillusioned many educated Chinese, thus further weakened the Qing government. After the Reforms ended, the conservative Empress Dowager Cixiseized power and placed the reformist Guangxu Emperor under house arrest. The European powers were sympathetic to the imprisoned emperor, and opposed Cixi's plan to replace him.[citation needed] By 1900, the great powers had already been chipping away at Chinese sovereignty for sixty years. They had forced China to import opium, thus leading to widespread addiction, defeated China in several wars, asserted a right to promote Christianity and imposed unequal treaties under which foreigners and foreign companies in China were accorded special privileges, extraterritorial rights and immunities from Chinese law, causing resentment and xenophobic reactions among the Chinese. France, Japan, Russia, and Germany carved out spheres of influence, so that by 1900 it appeared that China would likely be dismembered, with foreign powers each ruling a part of the country. Thus, by 1900, the Qing dynasty, which had ruled China for more than two centuries, was crumbling and Chinese culture was under assault by powerful and unfamiliar religions and secular cultures.[21] A Boxer during the revolt. 1900: A year of disastersBoxer rebels In January 1900, with a majority of conservatives in the Imperial Court, the Empress Dowager changed her long policy of suppressing Boxers, and issued edicts in their defense, causing protests from foreign powers. In Spring 1900, the Boxer movement spread rapidly north from Shandong into the countryside near Beijing. Boxers burned Christian churches, killed Chinese Christians, and intimidated Chinese officials who stood in their way. American MinisterEdwin H. Conger cabled Washington, “the whole country is swarming with hungry, discontented, hopeless idlers.” On 30 May the diplomats, led by British Minister Claude Maxwell MacDonald, requested that foreign soldiers come to Beijing to defend the legations. The Chinese government reluctantly acquiesced, and the next day more than 400 soldiers from eight countries disembarked from warships and traveled by train to Beijing from Tianjin. They set up defensive perimeters around their respective missions.[22] On 5 June, the railroad line to Tianjin was cut by Boxers in the countryside and Beijing was isolated. On 13 June, a Japanese diplomat was murdered by the soldiers of General Dong Fuxiang and that same day the first Boxer, dressed in his finery, was seen in the Legation Quarter. The German Minister, Clemens von Ketteler, and German soldiers captured a Boxer boy and inexplicably executed him.[23] In response, thousands of Boxers burst into the walled city of Beijing that afternoon and burned many of the Christian churches and cathedrals in the city. American and British missionaries had taken refuge in the Methodist Mission and an attack there was repulsed by American Marines. The soldiers at the British Embassy and German Legations shot and killed several Boxers,[24] alienating the Chinese population of the city and nudging the Qing government toward support of the Boxers. The Muslim Kansu braves and Boxers, along with other Chinese then attacked and killed Chinese Christians around the legations in revenge for foreign attacks on Chinese.[25] [edit]Conflicting attitudes within the Imperial CourtQing Imperial soldiers during the boxer rebellion.

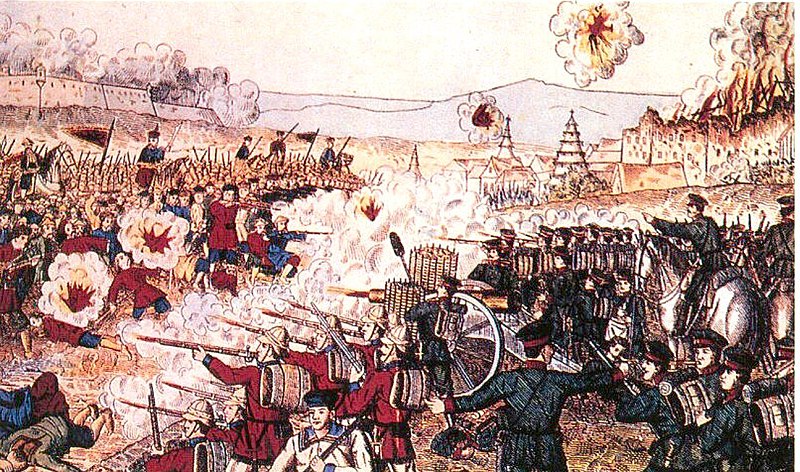

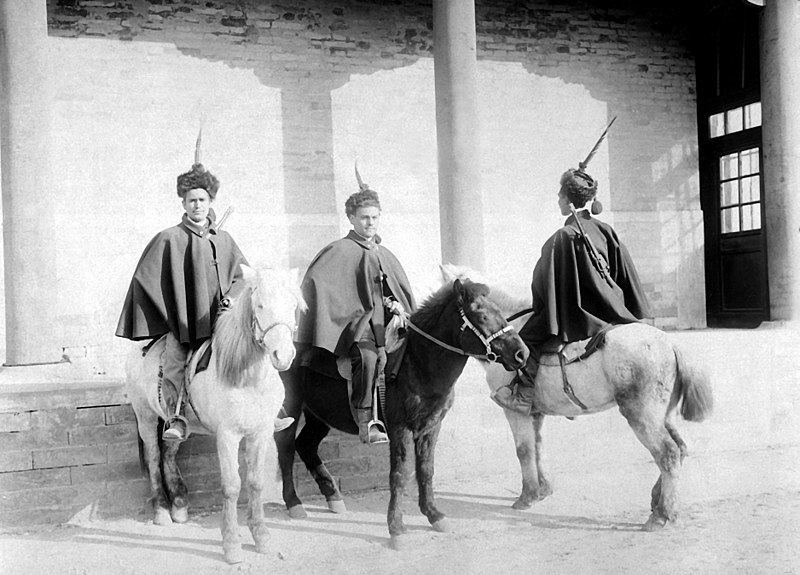

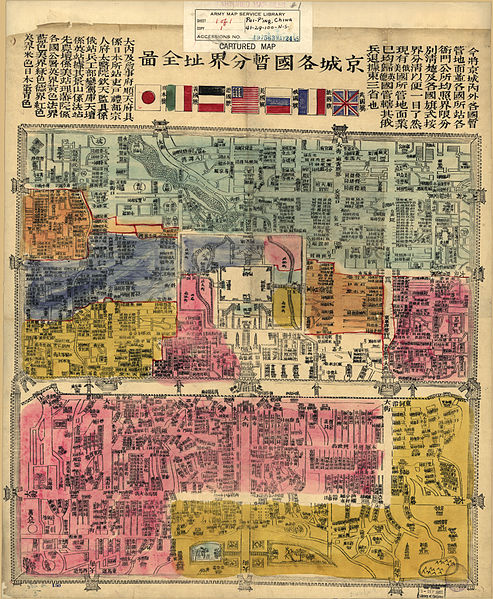

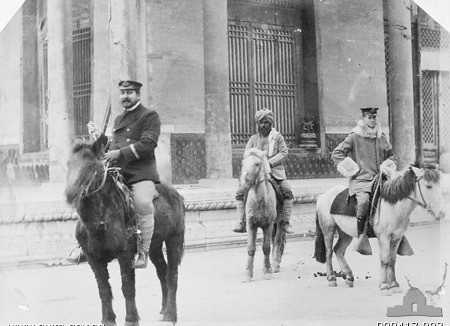

On 16 or 17 June 1900, the Emperor and the Empress Dowager held a mass audience for high officials to hear their opinions of whether the strategy towards the Boxers should be to pacify them or to suppress them. In response to a high official who doubted the efficacy of the Boxers' magic, Cixi replied that, "Perhaps their magic is not to be relied upon; but can we not rely on the hearts and minds of the people? Today China is extremely weak. We have only the people's hearts and minds to depend upon. If we cast them aside and lose the people's hearts, what can we use to sustain the country?" Both sides of the debate at court realized that popular support for the Boxers in the countryside was almost universal and that suppression would be both difficult and unpopular.[26] Italian mounted infantry near Tientsin in 1900. The Chinese government was split into two factions: the conservative traditionalists who wished to use the Boxers to remove foreigners from China and the moderates, who recognized China's weak position or wished to use diplomacy. Reflecting this inconsistency, some Chinese soldiers were quite liberally firing at foreigners under siege from its very onset. The Dowager Empress did not personally order Chinese Imperial troops to conduct a siege, and on the contrary had ordered them to protect the foreigners in the legations. Prince Duan led the Boxers to loot his enemies within the Imperial court and the foreigners, although Imperial authorities expelled Boxer troops after they were let into the city and went on a looting rampage against both the foreign and the Chinese Imperial forces. Older aged Boxers were sent outside Beijing to halt the approaching foreign armies, while younger men were absorbed into the Muslim Kansu army.[27] With conflicting allegiances and priorities motivating the various forces inside Beijing, the situation in the city became increasingly confused. The foreign legations continued to be surrounded by both Imperial and Kansu forces. While Dong Fuxiang's Kansu army, now swollen by the addition of the Boxers, wished to press the siege, Ronglu's Imperial forces seem to have largely attempted to follow the Dowager Empress's decree and protect the legations. However, to satisfy the conservatives in the Chinese imperial court Ronglu's men also fired on the legations and let off firecrackers to give the impression that they, too, were attacking the foreigners. Inside the legations and out of communication with the outside world, the foreigners simply fired on any targets that presented themselves, including messengers from the Chinese court, civilians and besiegers of all persuasions.[28] When Cixi received an ultimatum demanding that China surrender total control over all its military and financial affairs to foreigners,[29] she defiantly stated before the entire Grand Council, "Now they [the Powers] have started the aggression, and the extinction of our nation is imminent. If we just fold our arms and yield to them, I would have no face to see our ancestors after death. If we must perish, why not fight to the death?"[30] It was at this point that Cixi began to blockade the legations with the Peking Field Force armies, which began the siege. Cixi stated that "I have always been of the opinion, that the allied armies had been permitted to escape too easily in 1860. Only a united effort was then necessary to have given China the victory. Today, at last, the opportunity for revenge has come.", and said that millions of Chinese would join the cause of fighting the foreigners since the Manchus had provided "great benefits" on China.[31] The event that tilted the Imperial Government irrevocably toward support of the Boxers and war with the foreign powers was the attack of foreign navies on the Dagu Forts near Tianjin, on June 17. [edit]Siege of the LegationsMain article: Siege of the International Legations Locations of foreign diplomatic legations and front lines in Beijing during the siege. The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were located in the Beijing Legation Quarter south of the Forbidden City. On receipt of the news of the attack on the Dagu Forts on 19 June, the Empress Dowager immediately sent an order to the legations that the diplomats and other foreigners depart Beijing under escort of the Chinese army within 24 hours.[32] The next morning, the German envoy, Klemens Freiherr von Ketteler, was killed on the streets of Beijing by a Manchu captain.[33] The other diplomats feared they also would be murdered if they left the legation quarter and they defied the Chinese order to depart Beijing. The legations were hurriedly fortified. Isolated legations, such as the Spanish and Belgian, and foreign businesses were abandoned.[citation needed] Most of the foreign civilians, which included a large number of missionaries and businessmen, took refuge in the British legation, the largest of the diplomatic compounds.[citation needed] Chinese Christians were primarily housed in the adjacent palace (Fu) of Prince Su who was forced to abandon his property by the foreign soldiers.[citation needed] On 21 June, Empress Dowager Cixi declared war against all foreign powers. Regional governors who commanded substantial modernized armies, such as Li Hongzhang at Canton, Yuan Shikai in Shandong, Zhang Zhidong at Wuhan, and Liu Kunyi at Nanjing, refused to join in the Imperial Court's declaration of war and withheld knowledge of it from the public in the south. Yuan Shikai used his own forces to suppress Boxers in Shandong, and Zhang entered into negotiations with the foreigners in Shanghai to keep his army out of the conflict. The neutrality of these provincial and regional governors left the majority of China out of the conflict.[34] 1900, soldiers burned down the Temple,Shanhaikuan. The destruction of a Chinese temple on the bank of the Pei-Ho, byAmédée Forestier The Chinese army and Boxer irregulars besieged the Legation Quarter from 20 June to 14 August 1900. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge there.[35] Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with small arms, three machine guns, and one old muzzle-loaded cannon, which was nicknamed the International Gun because the barrel was British, the carriage Italian, the shells Russian, and the crew American. Chinese Christians in the legations led the foreigners to the cannon and it proved important in the defense. Also under siege in Beijing was the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) of the Catholic Church. The Beitang was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 Catholic foreign priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties especially from lack of food and mines which the Chinese exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound.[36] The number of Chinese soldiers and Boxers besieging the Legation Quarter and the Beitang is unknown, but certainly there were many thousands. On 22 and 23 June Chinese soldiers and Boxers set fire to areas north and west of the British Legation, using it as a "frightening tactic" to attack the defenders. The nearby Hanlin Academy, a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world," caught fire. Each side blamed the other for the destruction of the invaluable books it contained.[37] After the failure to burn out the foreigners, the Chinese army adopted an anaconda-like strategy. The Chinese build barricades surrounding the Legation Quarter and advanced, brick by brick, on the foreign lines, forcing the foreign soldiers to retreat a few feet at a time. This tactic was especially used in the Fu, defended by Japanese and Italian soldiers and inhabited by most of the Chinese Christians. Fusillades of bullets, artillery, and firecrackers were directed against the Legations almost every night -– but did little damage. Sniper fire took its toll among the foreign soldiers. Despite, however, their advantage in numbers, the Chinese did not attempt a direct assault on the Legation Quarter although in the words of one of the besieged, "it would have been easy by a strong, swift movement on the part of the numerous Chinese troops to have annihilated the whole body of foreigners... in an hour."[38] American missionaryFrank Gamewell and his crew of "fighting persons" played an invaluable role in fortifying the Legation Quarter.[39] Gamewell impressed Chinese Christians to do most of the physical labor of building defenses.[40] The Germans and the Americans occupied perhaps the most crucial of all defensive positions: the Tartar Wall. Holding the top of the 45 ft (14 m) tall and 40 ft (12 m) wide wall was vital. The German barricades faced east on top of the wall and 400 yd (370 m) west were the west-facing American positions. The Chinese advanced toward both positions by building barricades even closer. "The men all feel they are in a trap," said the American commander, Capt. John T. Myers, "and simply await the hour of execution."[41] On 30 June, the Chinese forced the Germans off the Wall, leaving the American Marines alone in its defense. At the same time, a Chinese barricade was advanced to within a few feet of the American positions and it became clear that the Americans had to abandon the wall or force the Chinese to retreat. At 2 am on 3 July, 56 British, Russian, and American soldiers under the command of Myers launched an assault against the Chinese barricade on the wall. The attack caught the Chinese sleeping, killed about 20 of them, and expelled the rest of them from the barricades.[42] The Chinese did not attempt to advance their positions on the Tartar Wall for the remainder of the siege.[43] Sir Claude MacDonald said 13 July was the "most harassing day" of the siege.[44] The Japanese and Italians in the Fu were driven back to their last defense line. The Chinese detonated a mine beneath the French Legation pushing the French and Austrians out of most of the French Legation.[45] On 16 July, the most capable British officer was killed and the journalist George Ernest Morrison was wounded.[46] But American Minister Edwin Hurd Conger established contact with the Chinese government and on 17 July, an armistice was declared by the Chinese.[47] More than 40% of the legation guards were dead or wounded. The motivation of the Chinese was probably the realization that an allied force of 20,000 men had landed in China and retribution for the siege was at hand. The armistice, although occasionally broken, endured until 13 August when, with an allied army approaching Beijing to relieve the siege, the Chinese launched their heaviest fusillade on the Legation Quarter. As the foreign army approached, Chinese forces melted away. The British Army reached the legation quarter on the afternoon of 14 August and relieved the Legation Quarter. The Beitang was relieved on 16 August, first by Japanese soldiers and then, officially, by the French.[48] [edit]Generals at cross purposesThe Manchu General Ronglu concluded that it was futile to fight all of the powers simultaneously, and declined to press home the siege.[49] The Manchu prince Zaiyi, an anti-foreign friend of Dong Fuxiang, wanted artillery for Dong's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from attacking.[50] Ronglu and Prince Qing sent food to the legations, and used their Manchu Bannermen to attack the Muslim Kansu Braves of Dong Fuxiang and the Boxers who were besieging the foreigners. They issued edicts ordering the foreigners to be protected, but the Kansu warriors ignored it, and fought against Bannermen who tried to force them away from the legations. Ronglu also deliberately hid an Imperial Decree from General Nie Shicheng. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers because of the foreign invasion, and also because the population was suffering. Due to Ronglu's actions, General Nie continued to fight the Boxers and killed many of them even as the foreign troops were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers.[51] Because parts of the Railway were saved under Ronglu's orders, the foreign invasion army was able to transport itself into China quickly. General Nie committed thousands of troops against the Boxers instead of against the foreigners. Nie was already outnumbered by the Allies by 4,000 men. General Nie was blamed for attacking the Boxers, as Ronglu let Nie take all the blame. At the Battle of Tianjin (Tientsin), General Nie decided to sacrifice his life by walking into the range of Allied guns.[52] Massacre of missionaries and Chinese ChristiansProtestant, Catholic, and Orthodox missionaries and their Chinese converts were massacred throughout northern China, some by Boxers and others by government troops and authorities. After the declaration of war on Western powers in June 1900, Yuxian, who had been named governor of Shanxi in March of that year, implemented a brutal anti-foreign and anti-Christian policy. On 9 July, reports circulated that he had executed forty-four foreigners (including women and children) from missionary families whom he had invited to the provincial capital Taiyuan under the promise to protect them.[53]Although the purported eye witness accounts have recently been questioned as improbable, this event became a notorious symbol of Chinese madness, known as the Taiyuan Massacre.[54] By the summer's end, more foreigners and as many as 2,000 Chinese Christians had been put to death in the province. Journalist and historical writer Nat Brandt has called the massacre of Christians in Shanxi "the greatest single tragedy in the history of Christian evangelicalism."[55] A total of 136 Protestant missionaries and 53 children were killed, and 47 Catholic priests and nuns. Thirty thousand Chinese Catholics, 2,000 Chinese Protestants, and 200 to 400 of the 700 Russian Orthodox Christians in Beijing were estimated to have been killed. Collectively, the Protestant dead were called theChina Martyrs of 1900.[56] The Boxers went on to murder Christians across 26 prefectures.[57] One specific rampage was set off after the German diplomat Clemens von Ketteler beat a Chinese boy to death. Anger against Chinese Christians set off again, and the Boxers burned down several churches, roasting some victims alive.[58] [edit]Evacuation of Imperial Court from Beijing to Xi'anIn the early hours of 15 August, just as the Foreign Legations were being relieved, the Empress Dowager, dressed in the padded blue cotton of a farm woman, the Emperor Guangxu, and a small retinue climbed into three wooden ox carts and escaped from the city covered with rough blankets. Legend has it that the Empress Dowager then either ordered that the Emperor's favorite,Consort Zhen the Pearl Concubine, be thrown down a well in the Forbidden City or tricked her into drowning herself. The journey was made all the more arduous by the lack of preparation, but the Empress Dowager insisted this was not a retreat, rather a "tour of inspection." After weeks of travel, the party arrived in Xi'an in Shaanxi province, beyond protective mountain passes where the foreigners could not reach, deep in Chinese Muslim territory and protected by the Kansu Braves. The foreigners were unable to pursue, and had no such orders to do so, so they decided no action should be taken. The allied interventions and the Boxer War Forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance Painting of Western and Japanese troops Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. Several international forces were sent to the capital, with various success, and the rebellion was ultimately quashed by the Eight-Nation Alliance of Austria-Hungary, France,Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. [edit]First international forceOn 31 May, before the sieges had started and upon the request of foreign embassies in Beijing, an international force of 435 navy troops from eight countries were dispatched by train from Dagu (Taku) to the capital (75 French, 75 Russian, 75 British, 60 U.S., 50 German, 40 Italian, 30 Japanese, 30 Austrian). After covering the 80 miles distance to the capital, these troops joined the legations and were able to contribute to their defense. [edit]Seymour ExpeditionMain article: Seymour Expedition Japanese marines who served in theSeymour Expedition. As the situation worsened, a second international force of 2,000 sailors and marines under the command of the British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour, the largest contingent being British, was dispatched from Dagu to Beijing on 10 June. The troops were transported by train from Dagu to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway between Tianjin and Beijing had been severed. Seymour resolved to move forward and repair the railway, or progress on foot if necessary, keeping in mind that the distance between Tianjin and Beijing was only 120 km. However, Seymour left Tianjin, and started toward Beijing, which angered the Chinese Imperial court. As a result, the Pro Boxer Manchu Prince Duan became leader of the Zongli Yamen (foreign office), replacing Prince Ching; orders were then given to Imperial army to attack the foreign forces. Confused by conflicting orders from Beijing, Chinese General Nie let Seymour's army pass by in their trains.[61] After leaving Tianjin, the convoy was surrounded, the railway behind and in front of them was destroyed, and they were attacked from all parts by Chinese irregulars and even Chinese governmental troops. News arrived on 18 June regarding attacks on foreign legations. Seymour decided to continue advancing, this time along the Beihe river, toward Tongzhou, 25 km from Beijing. By the 19th, they had to abandon their efforts due to progressively stiffening resistance and started to retreat southward along the river with over 200 wounded. Commandeering four civilian Chinese junks along the river, they loaded all their wounded and remaining supplies onto them and pulled them along with ropes from the riverbanks. By this point they were very low on food, ammunition and medical supplies. Luckily, they then happened upon The Great Xigu Arsenal, a hidden Qing munitions cache of which the Allied Powers had had no knowledge until then. They immediately captured and occupied it, discovering not only Krupp field guns, but rifles with millions of rounds in ammunition, along with millions of pounds of rice and ample medical supplies. Admiral Seymour returning to Tianjin with his wounded men, on 26 June. There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant was able to infiltrate through the Boxer and Qing lines, informing the Eight Powers of their predicament. Surrounded and attacked nearly around the clock by Qing troops and Boxers, they were at the point of being overrun. On 25 June, a regiment composed of 1800 men, (900 Russian troops from Port-Arthur, 500 British seamen, with an ad hoc mix of other assorted Alliance troops) finally arrived. Spiking the mounted field guns and setting fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimated £3 million worth), they departed in the early morning of 26 June, with 62 killed and 228 wounded.[62] [edit]Gaselee ExpeditionMain article: Gaselee Expedition The Boxers bombarded Tianjin in June 1900, and Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops attacked the British Admiral Seymour and his expeditionary force. With a difficult military situation in Tianjin and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June they took the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore. The international force with British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaselee acting as the commanding officer of the Eight-Nation Alliance, eventually numbered 55,000, with the main contingent being composed of Japanese soldiers: Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), U.S.(3,420), German (900), Italian (2080), Austro-Hungarian (75) and anti-Boxer Chinese troops.[63] The international force finally captured Tianjin on 14 July under the command of the Japanese Colonel Kuriya, after one day of fighting. The capture of the southern gate of Tianjin. British troops were positioned on the left, Japanese troops at the centre, French troops on the right. Notable exploits during the campaign were the seizure of the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Roger Keyes. Among the foreigners besieged in Tianjin was a young American mining engineer named Herbert Hoover.[64] The march from Tianjin to Beijing of about 120 km consisted of about 20,000 allied troops. On 4 August, there were approximately 70,000 Imperial troops with anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. The allies only encountered minor resistance, fighting battles at Beicang andYangcun. At Yangcun, the 14th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. The weather was a major obstacle, extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 110 °F (43 °C). Corporal Titus scaling the walls of Peking. The international force reached and occupied Beijing on 14 August. All the nationalities in the international force raced to be the first to liberate the besieged Legation Quarter with the British winning the race. The U.S. was able to play a minor role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion due to the presence of U.S. ships and troops deployed in the Philippines, which had been stationed there since the U.S. conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish American War and the subsequent Philippine Insurrection. In the U.S. military, the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition. American soldiers scaling the walls of Beijing is an iconic image of the Boxer Rebellion.[65] [edit]Russian invasion of ManchuriaRussian troops in Manchuria during the boxer rebellion The Russian Empire and the Qing Empire had maintained a long peace, starting with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, but Czarist forces took advantage of Chinese defeats to impose the Aigun Treaty of 1858 and the Treaty of Peking of 1860 which ceded territory in Manchuria much of which is held by Russia to the present day. The Russians aimed for control over Amur River for navigation, and the all weather ports of Dairen and Port Arthur in theLiaodong peninsula. The rise of Japan as an Asian power provoked Russia's anxiety, especially in light of expanding Japanese influence in Korea. Following Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895, the Triple Intervention of Russia, Germany and France forced Japan to return the territory won in Liaodong, leading to a de facto Sino-Russian alliance. Local Chinese in Manchuria were incensed at these Russian advances and began to harass Russians and Russian institutions, such as the Chinese Eastern Railway. In June 1900, the Chinese bombarded the town of Blagoveshchensk on the Russian side of the Amur, and in retaliation, the Russians massacred several thousand Chinese and Manchus in that town. The Czar's government used the pretext of Boxer activity to move some 200,000 troops into the area to crush Boxers. The Chinese used arson to destroy a bridge carrying a railway and a barracks in 27 July. Boxers destroyed railways and cut lines for telegraphs and burned the Yantai mines.[66] In battles on the Amur river, Western newspapers reported that the Chinese forces treated Russian civilians leniently and allowed them to escape to Russia, even notifying that they should leave the war zone. By contrast, Russian Cossacks brutally killed civilians who tried to flee in the Chinese villages. In revenge for the attacks on Chinese villages, Boxer troops burned Russian towns and almost annihilated a Russian force at Tieling.[67] Russian forces quickly dispatched both Boxers and Chinese Imperial troops. By 21 September, Russian troops took Jilin in Shandong, and by the end of the month completely occupied Manchuria, where their presence was a major factor leading to the Russo-Japanese War. The Chinese Honghuzi bandits of Manchuria, who had fought alongside the Boxers in the war, did not stop when the Boxer rebellion was over, and continued guerilla warfare against the Russian occupation up to the Russo-Japanese war when the Russians were defeated by Japan. [edit]Aftermath

It has been suggested that Eight-Nation Alliance#Aftermath be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2012. [edit]Occupation, looting, and atrocities"The Fall of the Peking Castle" from September 1900. British and Japanese soldiers assaulting Chinese troops. The occupation of Beijing. British sector in yellow, French in blue, US in green and ivory, German in red, and Japanese in light green. Beijing, Tianjin, and other cities in northern China were occupied for more than one year by the international expeditionary force under the command of German General Alfred Graf von Waldersee. The German force arrived too late to take part in the fighting, but undertook several punitive expeditions to the countryside against the Boxers. Although atrocities by foreign troops were common, German troops in particular were criticized for their enthusiasm in carrying out Kaiser Wilhelm II’s words. On 27 July 1900, when Wilhelm II spoke during departure ceremonies for the German contingent to the relief force in China, an impromptu, but intemperate reference to the Hun invaders of continental Europe would later be resurrected by British propaganda to mock Germany during World War I and World War II.

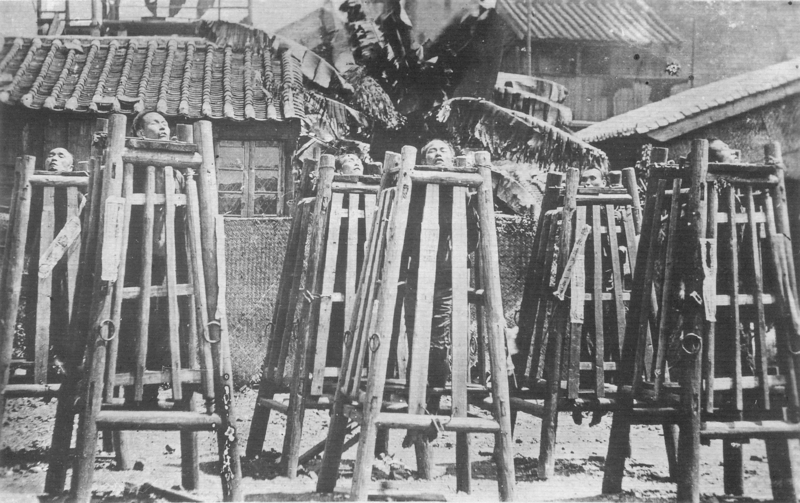

The Germans were not the only offenders. On behalf of Chinese Catholics, French troops ravaged the countryside around Beijing to collect indemnities—and on one occasion arresting American missionary William Scott Ament who beat them to the punch in gathering wealth from some villages.[69] Nor were the soldiers of other nationalities any better behaved. "The Russian soldiers are ravishing the women and committing horrible atrocities" in the sector of Beijing they occupied. The Japanese were noted for their skill in beheading Boxers or people suspected of being Boxers. General Chaffee commented, "It is safe to say that where one real Boxer has been killed... fifty harmless coolies or laborers on the farms, including not a few women and children, have been slain."[70] Japanese troops during the boxer rebellion American troops during the Boxer Rebellion. The intermediate aftermath of the siege in Beijing was what one newspaper called a "carnival of loot," and others called "an orgy of looting" by soldiers, civilians, and missionaries. These characterizations called to mind the sacking of the Summer Palace in 1860.[71] All of the nationalities in the expeditionary force engaged in looting,[72] but each nationality accused the others of being the worst looters. An American diplomat, Herbert G. Squiers, filled several railroad cars with loot. The British Legation held loot auctions every afternoon and proclaimed, "looting on the part of British troops was carried out in the most orderly manner." The Catholic Beitang or North Cathedral was a "salesroom for stolen property."[73] The American commander General Adna Chaffee banned looting by American soldiers, but the ban was ineffectual.[74] The missionaries were the most condemned. Mark Twain reflected American outrage against looting and imperialism in his essay, "To the Person Sitting in Darkness". American Board Missionary Ament was his target.[75] To provide restitution to missionaries and Chinese Christian families whose property had been destroyed, Ament guided American troops through villages to punish Boxers and confiscate their property. When Mark Twain read of this expedition, he wrote a scathing attack on the "Reverend bandits of the American Board."[76] Ament was one of the most respected and courageous missionaries in China and the controversy between him and Mark Twain was front page news during much of 1901. Ament's counterpart on the distaff side was doughty British missionary Georgina Smith who presided over a neighborhood in Beijing as judge and jury.[77] One witness recalled that "[t]he conduct of the Russian soldiers is atrocious, the French are not much better, and the Japanese are looting and burning without mercy".[72] It was reported that Japanese troops were astonished by other Alliance troops raping civilians; Japanese officers had brought along Japanese prostitutes to stop their troops from raping Chinese civilians.[78] Thousands of Chinese women committed suicide; The Daily Telegraph journalist E. J. Dillon stated it was to avoid rape by Alliance forces, and he witnessed the mutilated corpses of Chinese women who were raped and killed by the Alliance troops. The French commander dismissed the rapes, attributing them to "gallantry of the French soldier". A foreign journalist, George Lynch, said "there are things that I must not write, and that may not be printed in England, which would seem to show that this Western civilization of ours is merely a veneer over savagery."[72][79] [edit]ReparationsAfter the capture of Peking by the foreign armies, some of the Dowager Empress's advisers advocated that the war be carried on, arguing that China could have defeated the foreigners as it was disloyal and traitorous people within China who allowed Beijing and Tianjin to be captured by the Allies, and that the interior of China was impenetrable. They also recommended that Dong Fuxiang continue fighting. The Dowager was practical, however, and decided that the terms were generous enough for her to acquiesce when she was assured of her continued reign after the war and that China would not be forced to cede any territory.[80] On 7 September 1901, the Qing court agreed to sign the "Boxer Protocol" also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China. The protocol ordered the execution of 10 high-ranking officials linked to the outbreak and other officials who were found guilty for the slaughter of foreigners in China. Alfons Mumm (Freiherr von Schwarzenstein), Ernest Satow and Komura Jutaro signed on behalf of Germany, Britain and Japan respectively. China was fined war reparations of 450,000,000 taels of fine silver (1 tael = 1.2 troy ounces) for the loss that it caused. The reparation was to be paid within 39 years, and would be 982,238,150 taels with interest (4 percent per year) included. To help meet the payment it was agreed to increase the existing tariff from an actual 3.18 percent to 5 percent, and to tax hitherto duty-free merchandise. The sum of reparation was estimated by the Chinese population (roughly 450 million in 1900), to let each Chinese pay one tael. Chinese custom income and salt tax were enlisted as guarantee of the reparation. China paid 668,661,220 taels of silver from 1901 to 1939, equivalent in 2010 to ~US$61 billion on a purchasing power parity basis (see Tael).[81] Execution of Boxers after the rebellion. A large portion of the reparations paid to the United States was diverted to pay for the education of Chinese students in U.S. universities under the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. To prepare the students chosen for this program an institute was established to teach the English language and to serve as a preparatory school. When the first of these students returned to China they undertook the teaching of subsequent students; from this institute was born Tsinghua University. Some of the reparation due to Britain was later earmarked for a similar program. The China Inland Mission lost more members than any other missionary agency:[82] 58 adults and 21 children were killed. However, in 1901, when the allied nations were demanding compensation from the Chinese government, Hudson Taylor refused to accept payment for loss of property or life in order to demonstrate the meekness and gentleness of Christ to the Chinese.[83] The French Catholic vicar apostolic, Msgr. Alfons Bermyn wanted foreign troops garrisoned in inner Mongolia, but the Governor refused. Bermyn petitioned the Manchu Enming to send troops to Hetao where Prince Duan's Mongol troops and General Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops allegedly threatened Catholics. It turned out that Bermyn had created the incident as a hoax.[84][85] The Qing did not capitulate to all the foreign demands. The Bannerman Governor Yuxian was executed, but the Imperial court refused to execute the Chinese General Dong Fuxiang, although both had encouraged the killing of foreigners during the rebellion. Instead, Dong Fuxiang lived a life of luxury and power in "exile" in his home province of Gansu.[86] In addition to sparing Dong Fuxiang, the Qing also refused to exile the Boxer supporter Prince Duan to Xinjiang, as the Allies demanded. Instead, he moved to Alashan, west of Ningxia, and lived in Wangyeh Fu, where the local Mongol Prince lived. He then moved to Ningxia during the Xinhai Revolution when the Muslims took control of Ningxia, and finally, moved to Xinjiang with Sheng Yun.

|

PEKING, CHINA. 1900. A 16 YEAR OLD CHINESE GIRL WHO CARRIED MESSAGES BETWEEN PEKING AND TIENTSIN FOR THE BRITISH LEGATION DURING THE BOXER REBELLION

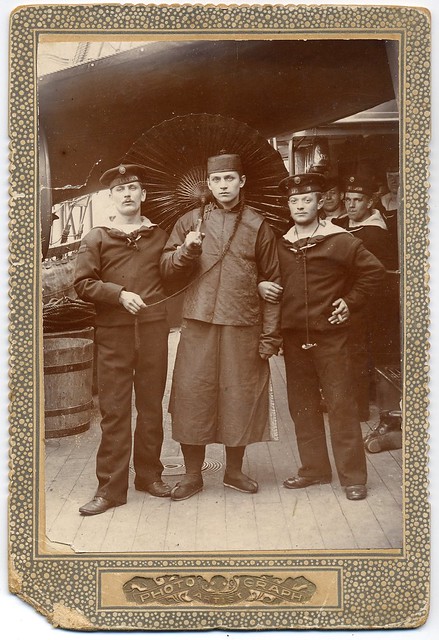

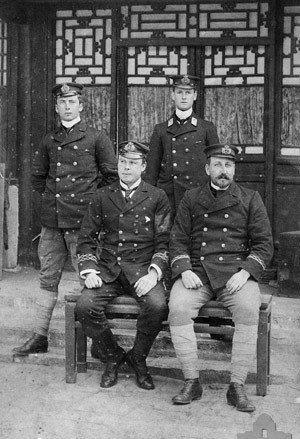

Austro-Hungarian Sailors In China

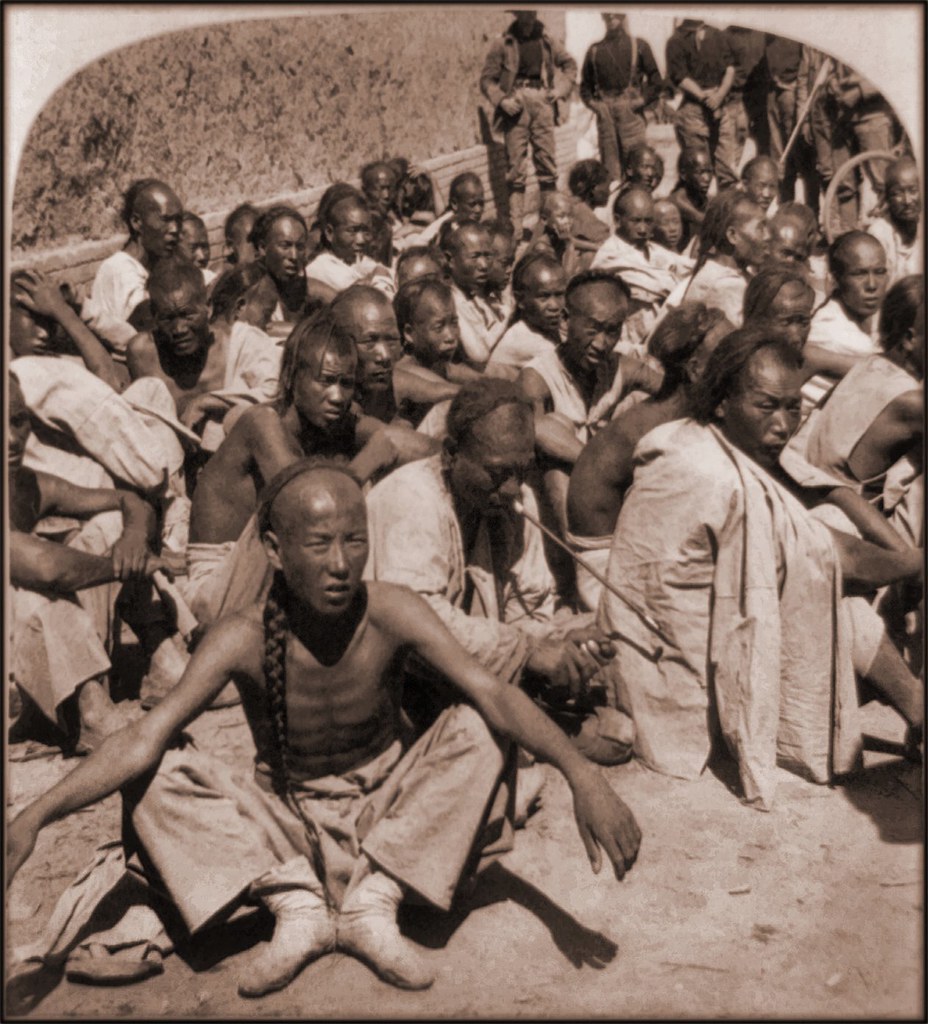

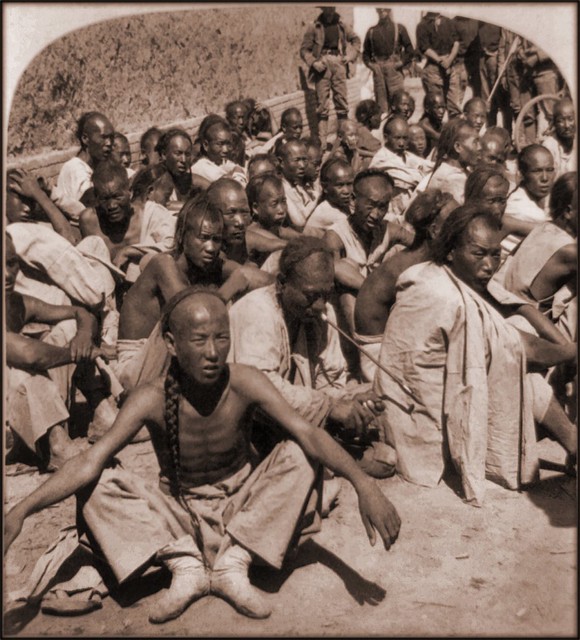

Boxer Prisoners Captured By 6th US Cavalry, Tientsin, China [1901] Underwood & Co [RESTORED]Entitled: Some of China's trouble-makers - "Boxer" prisoners captured and brought in by 6th U.S. Cavalry, Tientsin, China [1901] Underwood & Co. [RESTORED] The picture was retouched to eliminate spotting and obvious defects; tonal range was expanded to reveal better details in the shadows; cropped as single image from right side of double imaged stereoscope print, and mildly sepia toned. The title is not accurate, as it is now believed that most of the supposed Boxer prisoners caught by Foreign troops were just innocent bystanders. Nonetheless, the US Library of Congress, where this historic image resides (under Reproduction Number LC-USZ62-68811), maintains the original title as it was historically written or described by the person(s) that originally made or produced the photograph. Original was taken by a photographer employed by the Underwood & Underwood Company. Underwood was one of several companies at the time, whose business purpose was to send photographers to all parts of the world to photographically record interesting events in the hopes of selling the pictures to domestic customers. The double imaged pictures were recorded with a special stereo camera; that is, a camera fitted with two lenses side by side. This optical arrangement mimicked the natural and mildly divergent views of each eye that is necessary for human depth perception. When the resultant processed image was placed at a correct distance from both eyes (using a standardized picture holder - viewer), it reproduced a false sense of depth perception. This effectively made the image seem three dimensional and slightly more authentic, giving the viewer a feeling that they were witnessing the actual real life event. Thousands of these stereoscopic photos were sold in their day, and many may still be found tucked away in the old forgotten boxes of a grandparent's basement or attic. Additionally, black and white photography at that time was limited in terms of how the film perceived the colors of the spectrum. Most films were termed orthochromatic, that is, the film was sensitive to the Blue and Greens but was a poor recorder of the Red end of the spectrum. Thus, the skin tone of darker Asians, especially those worked in the sun and were well tanned, tended to be rendered much darker. This gave many Chinese in early black and white photographs darker skin tones, making them appear more African than Asian. In later years, this phenomenon faded with the introduction of Panchromatic films; that is, film with emulsions that were equally sensitized to all the colors of the spectrum. This picture is a cue to a lot of history. Taken about one year after the suppression of the "Boxers" (as the Chinese participants were known to the foreigners) these men were reportedly captured from the surrounding areas outside of Tientsin, China. The foreign powers had sought to purge and punish the responsible participants that had brought about the rebellion the year before (in 1900). Knowing little and caring even less about the locals, the foreign troops stated mission was to raid supposed Boxer stronghold villages to capture criminal Boxer participants that were still at large and to bring them to justice. However, what they effectively engaged in was pillaging, rape, and razing operations; essentially reprisals for the Chinese wounding of the Europeans. Prisoners that were not killed outright were brought back into the city for show trials and public executions. These expeditions snared mostly farmers, field hands, and otherwise uninvolved and innocent local Chinese. Under agreement with a Qing government that was more worried with preserving its monarchy than to concern itself with jurisprudence, thousands of Chinese were thus rounded up and executed by either western military or an acquiescing Chinese imperial authority. This heinous treatment of the Chinese populace by foreigners drove home the point that the Qing were no longer able to control China, and within this perceived power vacuum, the stage for China's transformation into a republic was ultimately set.

CHINA, C. 1900. THE BOXER REBELLION - THE CONDEMNED MAN AWAITS THE EXECUTIONER'S BLOW, HELD DOWN READY FOR THE BLOW OF THE SWORD.

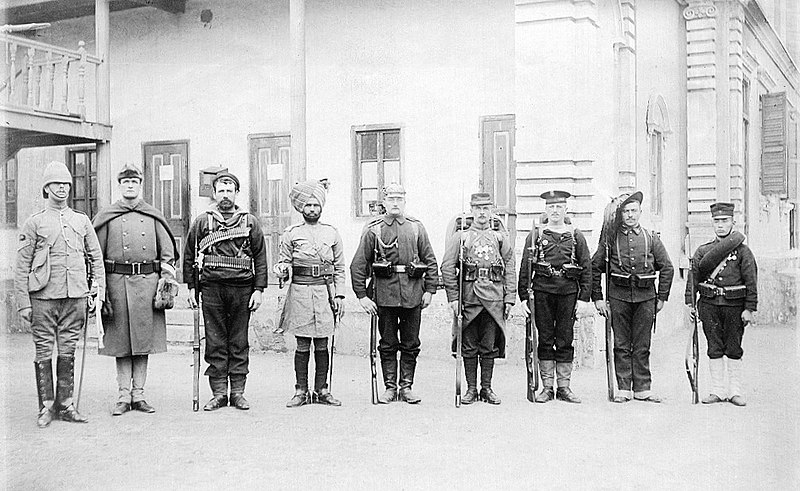

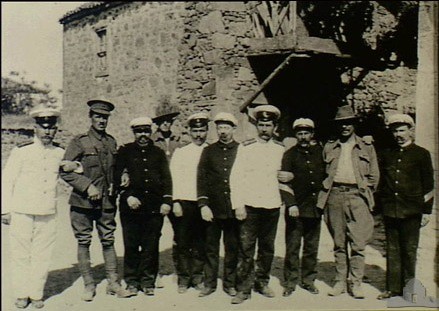

CHINA. A GROUP OF ALLIED FORCES WHO SERVED IN CHINA DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900 TO 1901

CHINA, 1900-1901. TWO OFFICERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL BRIGADE SERVING IN CHINA DURING THE BOXER REBELLION. ON RIGHT IS LIEUTENANT LEIGHTON S. BRACEGIRDLE

CHINA. A GROUP OF AUSTRALIAN NAVAL BRIGADE OFFICERS SERVING IN CHINA DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900-1901

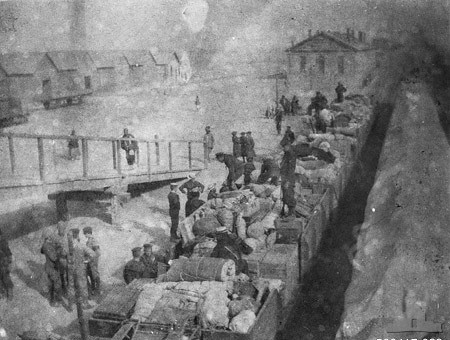

CHINA 1900-1901. DIPLOMATIC REFUGEES LOADING THEIR BELONGINGS UPON A TRAIN IN PEKING. TAKEN DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900-1901

CHINA. MEMBERS OF THE NSW CONTINGENT WITH MEMBERS OF OTHER ALLIED FORCES WHO SERVED WITH THEM DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900-1901

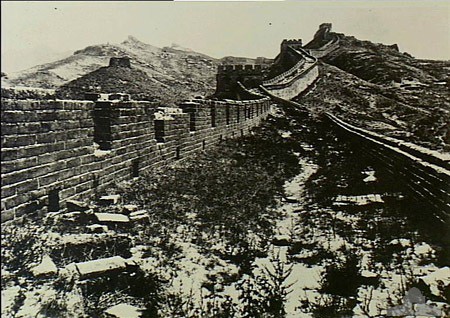

Peking, China. A section of the Great Wall of China during the period of the Boxer Rebellion, 1900-1901

Peking, China. A damaged (presumably by shellfire) section of the Great Wall of China at the time of the Boxer Rebellion, 1900-1901

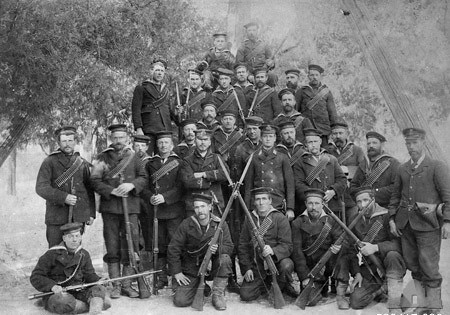

Peking, China, c 1900. Group portrait of Australian Naval Brigade who served in the Boxer Rebellion, 1900-1901.

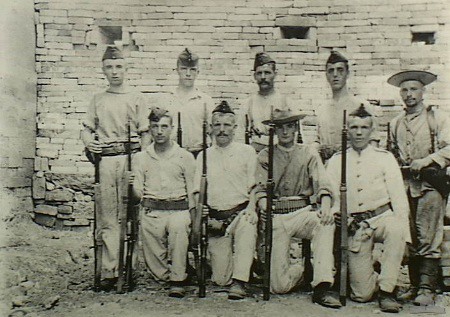

PEKING, CHINA. 1900. SEVEN MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL MARINE LIGHT INFANTRY (RMLI) AND ONE OF THE NAVAL BRIGADE DURING THE BOXER REBELLION

PEKING, CHINA. 1900. A GROUP OF ROYAL MARINE LIGHT INFANTRY MEMBERS WHO ASSISTED IN THE DEFENCE OF THE BRITISH LEGATION DURING THE BOXER REBELLION

LIEUTENANT LEIGHTON S. BRACEGIRDLE, WHO SERVED WITH THE NAVAL BRIGADE DURING THE BOXER REBELLION, 1900-1901

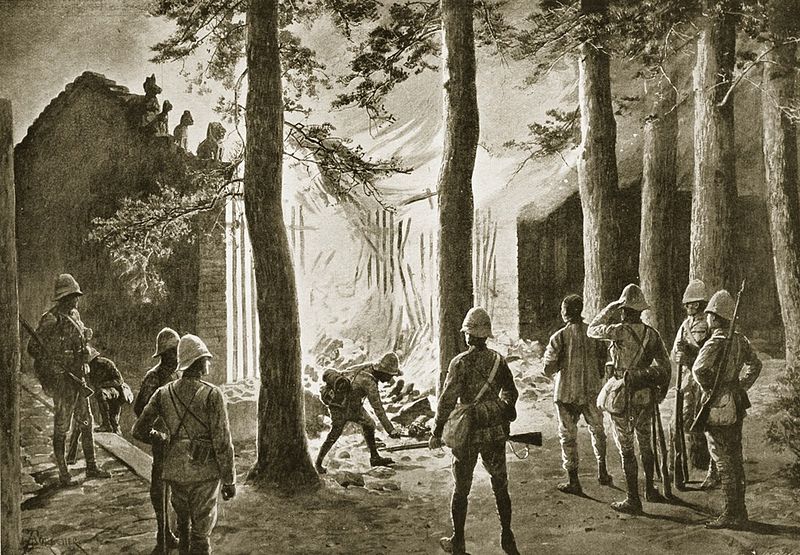

PEKING, CHINA. 1900. SCENE AT A TEMPLE WHERE FORTY NINE BOXER TROOPS WERE KILLED DURING THE BOXER REBELLION

CHINA, 1900-1901. MEMBERS OF THE NSW, 1900-1901

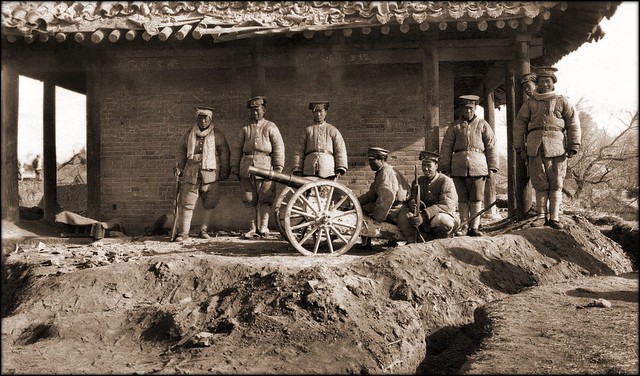

THE RAG-TAG FIGHTING BOXERS --- Responsible for Killing Tens of Thousands of Their Fellow Chinese (At Least That''s What the American Publisher Said !)The original caption from 1900 calls these fellows THE FIGHTING BOXERS in TIEN TSIN, CHINA. It is known that Ben Kilburn (see credit line at bottom of caption) wrote all of the descriptive titles for these images, based on either (1) information supplied by the photographer, or (2) captions he pulled out of thin air that he thought sounded good, or would sell the photos. Okinawa_Soba generally sticks to those original captions when rephrasing them for flickr. For most photos, on my photostream, that is sufficient. However, with this photo, there might be a problem with old Ben Kilburn''''s original description of the contents. Flickr commenter Ralphrepo gives a very good analysis of what the content more likely shows us : "..........<em>Hmmm... My suspicions are that these weren''''t so much "Boxers" as they were Qing irregulars, or local militia. Their headgear is imperial styled, and they''''re armed with blunderbusses, which boxers would have found hard or difficult to obtain in any quantity. Further, had these really been foreigner hating Boxers at the height of the conflict, the photographer''''s life would most likely have been imperiled. He would probably not have survived long enough to render the image. Since this image seems to be a part of the set taken by an "unknown" lensman from Kilburn View Company, and as the other picture shows uniformed imperial troops, I would lean towards Qing militia, that is, irregular troops under local command, usually loyal to the government, that the photographer then had authorized access to. However, during the rebellion, even imperial units followed their commanders more so than they did the Qing flag; that is, switching sides in the midst of battles were not uncommon depending on the loyalty of each particular leader and which side of the political bed he arose that morning on. Further, the Qing government itself wavered in its stance, suppressing the boxers initially but then supporting them, and in the end ruthlessly abandoning them to western justice. Some Imperial units even refused to get involved, retreating as far away from the fighting as possible. I doubt that the real identity of these fellows would ever be known</em>..........."

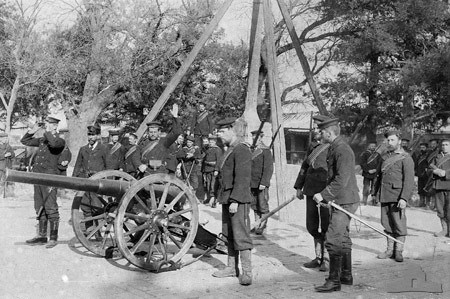

PEKING, CHINA. 1900. AN ARTILLERY PIECE AT THE BRITISH LEGATION, POSSIBLY A HOME MADE GUN KNOWN AS BOXER BILL

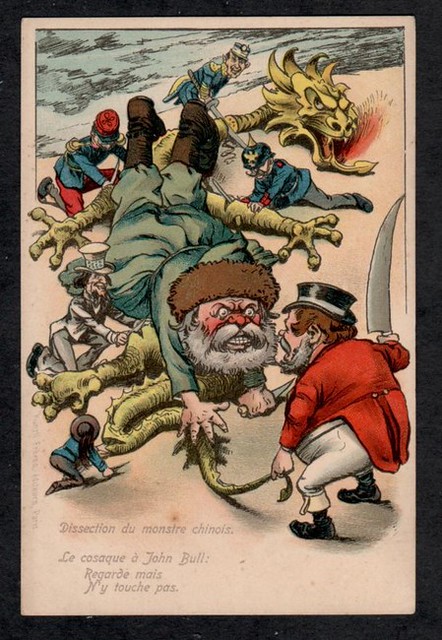

八国联军 Boxer Rebellion 1900English translation: Chinese dissection of the monster.

The Emperor's BirthdayCelebration of the German Emperor's Birthday on the S.M.S. Gefion in China during the Boxer Rebellion. Ca 1900, Kiautschou bay.

Yen's Soldiers, Militarism In China, Here Are Specimens Of The Soldiery Who Protect The People By Dominating Them, Who Protect Property By Looting It, Liao Chow, Shansi, China [c1925] IE Oberholtzer (probable) [RESTORED]Entitled Militarism in China. Here are specimens of the Soldiery who protect the people by dominating them, who protect property by looting it Liao Chow, Shansi, China [c1925] IE Oberholtzer (probable) [RESTORED] I did light scratch and spot repair, adjusted tone, contrast, added a sepia coloration, and cropped away the partial view of the individual on the far right edge. From a private collection discovered on Picassa Web Albums (Google's free picture gallery) as hosted by generous netizen Joe. He has a collection of images that (from what information I could gather on his gallery), seems to have been taken by one I.E. Oberholtzer in or around the Liao Chow area of Shansi, (I suspect this may be modern day Liaozhou, Shanxi Province, but I'm having a bit of difficulty getting cross referenced confirmation), China, during the 1920-1930s. Once again, it is due to the dedication of private citizens that images which would otherwise be lost to history, is instead seen by all. This validates and burnishes that part (in this case, of a part of China), and makes indelible an isolated stitch in the fabric of time. Woven together with the contributions of others, that fabric becomes a tapestry that testifies to our collective history in a vital visual record. We all hold a debt of gratitude to the generosity of such net contributors. Other pictures from this series and Joe's magnificent galleries can be seen here: picasaweb.google.com/LlamaLane Most people consider the China of today as a nation that has 5000 years of continuous unbroken history as one political entity; that is not so. As recent as a century ago, China was politically fractured akin to a nation say, like Pakistan, where the central government held political sway in name only. Genuine authority outside central urban areas resided in the hands of well financed individuals, called warlords, each armed with their own personal army. Warlords held their positions by strength of the sword, and areas under their control were effective fiefdoms that the Chinese central government had little or no control over. At times, even central government commerce movement needed to tender road tariffs to these local governments before being allowed passage. These regional governments functioned by their own rules, often created at the whim of their leader. They fought not only with the government but with each other. Between the years of 1912 and the second world war, most people understand and remember the national struggle between the communists and the nationalists in China. In fact, the nationalist government was only in nominal control, with the communists being but one external factor, along with a variety of warlord cliques and subordinate factions that competed for overall supremacy in 8 major geographic areas. Opportunistic coalitions often formed to work either against, or with the Nationalist government; though allegiances were well acknowledged to be something ephemeral as parties easily traded loyalties according to their individual needs of the moment. Regional armies with fidelity to a local leader instead of a national government wasn't an entirely new concept to the Chinese of the times. In fact this was business as usual as far as Chinese history was concerned. During the monarchy, Qing standing regional Bannermen armies could likewise have been a template for the Warlord phenomenon. Each Banner was separate and distinct from the others and only loyal to themselves, and not to any idea of national government, per se. They fought for the throne because they were paid to. Thus, they were similar to mercenary armies at the service of the government During this period of national crisis, Outer Mongolia, long a part of the Qing empire, (under strong Soviet influence) successfully broke free and became, de facto, independent from China in 1921 . The Chinese nationalists successfully kept Xinjiang and Xizang (aka Tibet) from breaking away, and were also successful in keeping most other nations from further colonizing what was essentially a broken and defenseless China. The Warlord private armies in essence were regionally raised militias that were privately trained. They were armed with a variety of western and traditional equipment and in one battle alone (Central Plains Battle of 1930, in which three warlords allied against the central Nationalist government), involved an estimated one million troops. These troops rode roughshod over the populace with impunity. They were notorious for robbing, raping, and pillaging everywhere they went. If they didn't have enough men to perform support functions (like build fortifications or carry away loot), they would gang impress local manpower as slave labor. They would often take whatever crops there were, and allowed the local population to subsist on starvation rations. As patronage mills, they allowed men of affluence to buy officer postings either for themselves or their sons, to serve as midlevel leaders within a warlord's army. The situation was so socially severe and dire that the populace hungered for relief and easily bought into the communist message of land ownership reform, equality of treatment, shared burden, and national defense. This helped set the stage for the mass support that Mao needed to overthrow the nationalists and take the country by force of arms. |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment